Splitting the Terraform monolith

At Digipost we are in the progress of building up our new infrastructure on Azure. We are already enthusiastic users of Terraform and have chosen to continue down that path, towards infrastructure-as-code (IaC) bliss, where the totality of your infrastructure can be created by a single command. But what happens when that totality is a bit big for a single Terraform state-file?

4 min read

·

By Gustav Karlsson

·

December 11, 2019

As we were building the new infrastructure and adding more and more components to our Terraform state, some operational pains started to surface. Operations were slower and recreating the stateless compute parts (Kubernetes) sometimes led to seemingly unrelated resources being affected, in part because the effective dependency graph was slightly accidental. As a response to these pains, we did some research to learn a bit more about best practices when structuring Terraform projects.

Splitting by environment

It turns out that especially in the early days of Terraform, bugs where Terraform crashed and messed up your state was not uncommon. This led to early adopters being concerned about the blast radius when running Terraform, in other words, if something explodes, how many resources will at maximum be affected. In the words of Charity Majors:

"It is still as green as the motherfucking Shire and you should assume that every change you make could destroy the world. So your job as a responsible engineer is to add guard rails, build a clear promotion path for validating changesets into production, and limit the scope of the world it is capable of destroying. This means separate state files.

https://charity.wtf/2016/03/30/terraform-vpc-and-why-you-want-a-tfstate-file-per-env/"

Though this was written back in March 2016 and Terraform has matured a lot since then, the point she makes is still valid and touch upon the scary thing about IaC: As easy as it is to create all your infra in one command, it is just as easy to tear it all down again. Which is why you need to think about what "guard rails" you have in place to make sure that never happens. One such guard rail, Charity suggests, is separate state-files per environment, enabling you to safely test out infrastructure changes in test environments as well as reducing the total number of resources in the state-file.

Splitting by component

Yevgeniy Brikman, creator of Terragrunt and another infra-veteran, goes further in the theme of blast radius reduction and "guard rails", and suggests to also separate state by component, so that resources that are changed frequently are not grouped together with stateful resources such as databases. In a blogpost he says:

"If you manage the infrastructure for both the VPC component and the web server component in the same set of Terraform configurations, you are unnecessarily putting your entire network topology at risk of breakage (e.g., from a simple typo in the code or someone accidentally running the wrong command) multiple times per day."

He suggests the following structure as a template for a Terraform project:

# Source https://blog.gruntwork.io/how-to-manage-terraform-state-28f5697e68fa

stage

└ vpc

└ services

└ frontend-app

└ backend-app

└ main.tf

└ outputs.tf

└ variables.tf

└ data-storage

└ mysql

└ redis

prod

└ vpc

└ services

└ frontend-app

└ backend-app

└ data-storage

└ mysql

└ redis

mgmt

└ vpc

└ services

└ bastion-host

└ jenkins

global

└ iam

└ s3Notice the additional directories under for example prod/. This will in addition to environments, isolate VPC, data stores, web-servers etc from each other. The drawback of such a layout is the increased complexity of operations when using many state-files (as Terraform need to be run in all the different subdirectories), and also the increased duplication of config. At this point, most seem to prefer using a wrapper like terragrunt or astro to ease the pain, while some prefer the wrapper-less approach.

Another benefit of splitting by components, or at least layers of similar components, is that it forces you to think more of what the interfaces between layers are, since you cannot reach back through the dependency graph and extract data from resources that now live in other state-files. And thus it will also be harder to accidentally introduce unwanted dependencies, for example from a database to a Kubernetes cluster.

So there seems to be a general consensus that you should both separate by environment and by groups of components. But how you keep the Terraform source DRY and how you rollout changes is where things get much more opinionated and dependent on things like team-size. The good thing though is that those things are easier to change as you go along, whereas moving resources between modules and state-files is a bit harder and better to get “as right as you can” from the start.

For those interested in a deeper dive into the topic, OpenCredo have written a great article about the different stages in their journey from a single state-file to a split-by-component setup. They loosely compare splitting by component to a monolith being broken into smaller micro-services.

So what did we do?

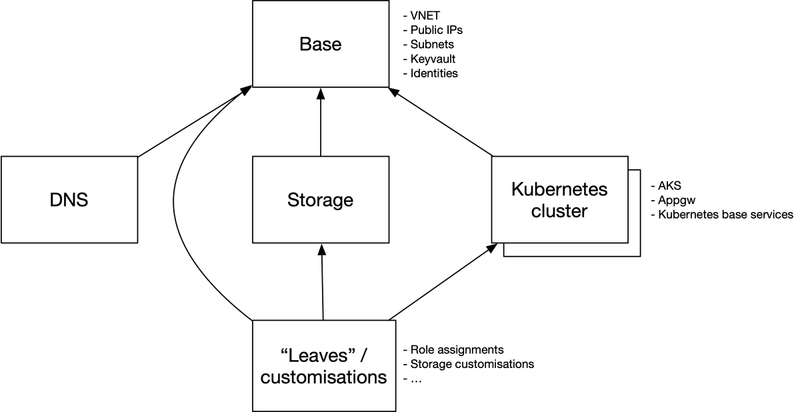

So what did we end up doing? We already had one state-file per environment, and decided to further separate it into layers of components to really isolate the stateful resources from frequent changes. It was a really useful exercise which made it clearer what resources belonged together and which did not. Below is a somewhat simplified illustration of our current state split.

We are particularly happy with having isolated the storage components into small stable state-files.

Hopefully this will make operations faster and safer and be a better foundation to evolve from.

Up next...

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…