Reinforcement learning

From the moment they’re born, animals learn by interacting with their surrounding environment. The basic question in the field of reinforcement learning is: can machines do the same?

5 min read

·

By Tharald Jørgen Stray

·

December 18, 2019

Machine learning is often divided into three basic paradigms: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning.

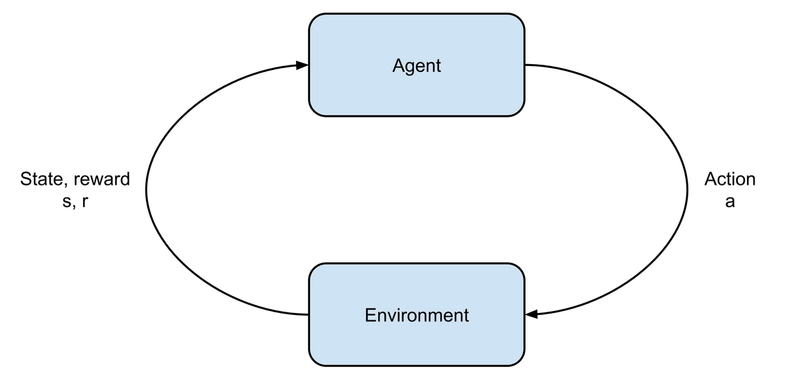

In reinforcement learning (RL), software agents are left to fend for themselves in environments with unknown dynamics, and must learn how to behave by observing how the environment changes as a result of previous states and actions taken. To be able to distinguish between good or bad behaviour, the agent receives rewards and punishments based on the state of the environment, and its own actions.

The policy dictates the behaviour of an agent. The ultimate goal in reinforcement learning is for the agent to learn a policy which will maximize some objective function, often the total reward gained. A value function is often used to keep track of the expected values of certain states, or state-actions pairs. The value function can often be used to derive optimal actions directly.

During training, the agent interacts with the environment, and subsequently updates its policy based on the interaction. This means that a reinforcement learning algorithm trains using a simulation of some scenario, as opposed to using labeled data, as in supervised learning.

In some cases, an agent can interact with the environment for multiple steps and episodes at a time, collecting the experiences in what is called a replay buffer. These experiences can then be used for training later. This allows training to be completed in batches, which can be much more effective, especially when neural networks are used as function approximators.

A complete environment run from its initial state until the end is called an episode. Episodes contain some number of discrete time steps, and at each time step the agent receives an observation from the environment, containing the new state and a reward value, and chooses an action, which is then executed in the environment. This repeats until some end condition is met.

Recently, the field of deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has seen a surge of interest in the academic world. Deep reinforcement learning simply refers to reinforcement learning algorithms which use deep neural networks as function approximators, mostly to represent the policies and value function discussed earlier.

The field of reinforcement learning has been around for a long time, but has had a limited set of practical applications. Maintaining state was often done by having a lookup table for all states, which is infeasible for large observation spaces. Using neural networks as function approximators was possible, but learning was unstable, and was considered to be computationally infeasible for complex problems.

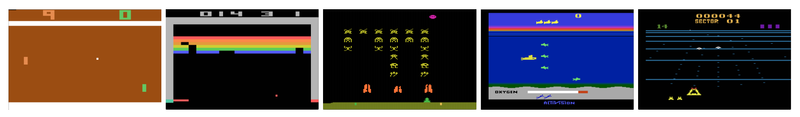

These were the main obstacles overcome in the Google DeepMind Deep Q-Networks paper (see relevant links), which is said to have sparked this wave of interest in the field of deep reinforcement learning. The paper also made it clear that reinforcement learning methods had huge potential in a popular field, namely games. Due to their deterministic nature and clearly defined rules, games make excellent reinforcement learning training environments.

The DQN paper, first published in 2013, showcased an approach which utilized deep neural networks as functions approximators at scale, in a popular RL algorithm known as Q-learning. DeepMind named the approach Deep Q-Networks (DQN), and trained an agent to play a wide range of Atari games (see image above) at a super-human level.

After a series of consecutive breakthroughs, DeepMind created AlphaZero, a general algorithm which could be trained to play games such as Go, Chess and Shogi, beating both human and computer program champions alike. You can read more about this in tomorrow's blog post.

These algorithms often start with a completely blank slate, tabula rasa. They create their policies from the ground up, without any preprogrammed baseline or rules created by humans. This allows the policies to be devoid of any human bias which is often introduced in algorithms designed explicitly by humans.

If one were to consider gameplay a war, it would be clear that the humans are losing. Deep reinforcement learning algorithms are starting to best humans at even more complicated games such as Dota 2 and StarCraft II, which include vast amounts of imperfect information and long-term strategizing, a combination which for a long time was considered infeasible for learning-based methods to overcome.

Interestingly, both of the approaches underpinning these algorithms, namely neural networks and reinforcement learning, are inspired by biology and nature. Neural networks started as an attempt to mimic the inner workings of the animal brain, and reinforcement learning is based on (a simplification of) how we believe animals learn. Stay tuned for tomorrow’s blog post, which will delve deeper into the potential of deep reinforcement learning by exploring one of the most sought after goals in all of AI: the quest for general intelligence.

For anyone looking for more in-depth resources, I strongly recommend checking out Spinning Up by OpenAI (link below). It includes theory, exercises, well documented implementations of cutting edge algorithms, and references to relevant papers and other resources. If you prefer purely theoretical resources, I would also like to recommend two great books: “Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction” by Sutton & Barto, and “Deep Reinforcement Learning: An Overview” by Yuxi Li.

Thanks for reading!

Up next...

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…