Hack your paleolithic mind to overcome stage fright

Most of us feel very uneasy before going on a stage or in front of a live tv-camera. Rationally you can tell yourself that even if it all goes wrong, in a few hours you will still be alive, that you’ll still have your friends and your job. And you’ll be right. Even if you forget what to say, stutter and run crying off stage, the actual impact on your life is not that important. It’s not a matter of life and death, is it?

4 min read

·

By Jens Andreas Huseby

·

December 9, 2020

As an evolutionary biologist who’s been fortunate to appear on some tv- and radio shows, I’ve wanted to understand why we feel so nervous before appearing in front of an audience and how to overcome it. To hack your stage fright away, you must first understand why your mind is designed this way.

Mismatch

Evolution is a very slow design process as it takes many generations for even the most important adaptations to become a part of our nature. Even fundamental traits like being able to digest a new easily available energy source will take one hundred thousand years to become common. As a result, our emotions are not perfectly designed to reflect how dangerous a situation really is in modern life. Speaking up in front of an audience is not a matter of life and death. Not now.. but it probably was in most of our earlier history. And because evolution takes ages to redesign us to match this new reality, “stage fright” is still part of our psychological wiring.

Our natural environment consists of people

Other humans and what they do are important parts of the environment for us humans. “People” is probably the most important environmental factor in our lives. To put it in evolutionary terms: the most important thing affecting the number of grandchildren a human could get, is other people. One of my favorite recent scientific discoveries highlight just how extremely wired we are to care about what other people think.

The Brain’s default mode network

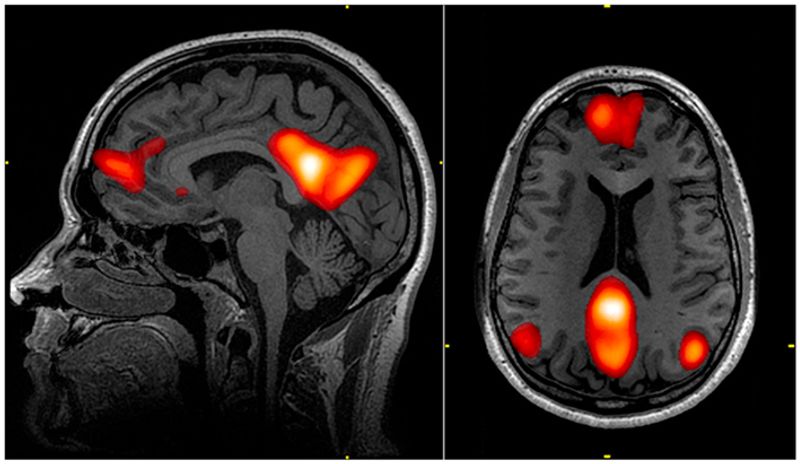

For several decades scientists have used MRI-machines to study how different areas in the brain get activated when a person is given a specific task. Some areas, aka “language centers”, light up when the research subject is asked to speak or read. Other areas are activated when solving math problems or listening to Beethoven.

But what happens in the brain when a person is resting? Does the brain deactivate?

Some researchers continued the scan after telling the person in the MRI-machine to relax. What they found was that other areas in the brain lit up. It turned out that this was not some random brain activity, but areas that are active in most people when they relax and do nothing. It’s like a default state that the brain returns to after finishing work. Because of this it was called “The Brain’s default mode network” and thought to be like a screensaver that keeps the brain healthy until it gets something useful to do again.

Only recently have neuroscientists discovered that the default mode network overlaps almost perfectly with the brain areas that get active when people think about their social relationships.

This is mindblowing. Literally.

Instead of going to a default “screensaver” when there is nothing better to do, our brain spends as much time as it can to think about other people. We simulate complex social relationships whenever we can. “What would he do if I said..”, “what if she knew, that I know..”, “how can I get back at that guy who told everyone that…”. This is what we, as humans, are designed to do when we relax.

(Ever sat down a friday evening with social media on your phone or a soap opera on TV? Yup. That’s you putting your brain’s default mode network to work.)

Stage fright

Other people’s opinion of us affect who we can form an alliance with, who will protect you, who will go against us, who you can attract as a partner, which opportunities you get and much more. This is far from trivial. These are central evolutionary problems (see our blog post ux.christmas/2019/4) for a social species such as ours. And that is why your brain and emotional systems get so fired up before talking to a crowd.

The hack(s)

So, doesn’t this mean that it’s only natural to be scared to death over a presentation? Yes, it does. But realizing this is helpful. Because you have to trick your paleolithic mind into believing it’s in a slightly different situation. Here’s how I do it:

- Pretend you’re just going to talk to your friends about something you know really well (and most of the time, this is sort of true)

- Try to feel like when you are about to give your friends a gift (you really are, by sharing something you know)

- Remember that you really know how to speak. You’ve done it almost every single day of your life

- Don’t worry about saying something wrong. Any mistakes you talk yourself into, you can talk yourself out of.

And if none of these hacks work: hey, you’ve found a cool and relatable topic for your next talk! Share it!

Up next...

Loading…