Fantasy Premier League with data science

Helping you pick the top team for Boxing Day!

7 min read

·

By Tobias R. Pettrém

·

December 23, 2019

If you’re a below-average Fantasy Premier League performer and an above-average data science enthusiast, we have at least two things in common – and you’ve found exactly the right article!

Picking the right Fantasy team with data science is no new subject,1 but we thought we’d give it a go and compare two classic prediction models: linear regression and a basic neural network. We’ll train the models on historical data, evaluate their performance, and finally set up our ultimate team for the pinnacle of Premier League – Boxing Day⚽

Both models are based on three steps. First, they are trained to predict expected amount of Fantasy points achieved by each Premier League player in any round, based on a set of input data. Second, the models try to predict the points scored by each player in an out-of-sample round. Third, the simplex algorithm is used to solve the LP problem of constructing a team of 11 players fulfilling the constraints given by the Fantasy rules, maximizing the number of expected points. Still hanging on? Let’s dive in!

1. Training the models

Input data

The models are trained using data provided by GitHub user Vaastav Anand, who publishes all Fantasy results and stats after each gameweek. The input parameteres for each individual player in any given round are:

- Position (four variables)

- Team (20 variables)

- Opponent team (20 variables)

- Home/away game (one variable)

- Form the last 5 games (Fantasy's own ICT index) (five variables)

This results in 50 input variables in total, with actual Fantasy points achieved in each round as the dependent variable. All data from previous rounds are used in the training phase to predict a given round (i.e., predicting results in round n, the training sample contains data from rounds n-1, n-2, ... , 1). Predicting round 19, data from rounds 1 to 17 was used.2

Designing the models

The linear regression is set up with the assumed weakest team as baseline on the team variable, and the assumed strongest team as baseline on the opponent team variable. An ordinary least squares regression is performed. The neural net uses four layers: input layer (50 neurons), two middle layers (50 and 30 neurons) and finally an output layer (one neuron). All layers use the relu activation function, except the output which uses a linear activation function. There is also added a dropout layer between the two middle layers with a dropout probability of 0.2. The model uses mean squared error as loss function and the Adam optimizer.

2. Predicting points

After the models are fitted, they predict points achieved by all the Premier League players in the out-of-sample round – in our case, round 19. Injured or suspended players are not predicted.

3. Selecting the XI

After predicting points scored by all players, the simplex algorithm is used to construct a team maximizing total expected points. The official Fantasy rules are set as constraints, including the £100m budget (however, as we will see, the models do not necessarily spend all their money). The cost of substitutes are accounted for by leaving at least enough money in the budget to buy the cheapest possible players filling up the 15-man squad, but they are not specifically selected (and consequently, no players are subbed on should any in the first XI not play). The player with the highest amount of expected points is set as captain, and the second highest as vice captain.

Results from earlier rounds

To examine the strength of our models, we let them predict already played rounds and compare their results with the average score of all human Fantasy players.3 The number of points achieved by the models in gameweek 13 to 17 is displayed in the table below:

As we see, the regression is remarkably consistent, beating the average score with at least 10 % each round. The neural network appears slighty more risk-seeking, resulting in highly varying scores ranging from a staggering round 16 score of 89 points to an equivalently disastrous performance in the previous round. However, both models outperform the average player over the course of five rounds. Let's have a look at their bets for Boxing Day!

Gameweek 19 predictions

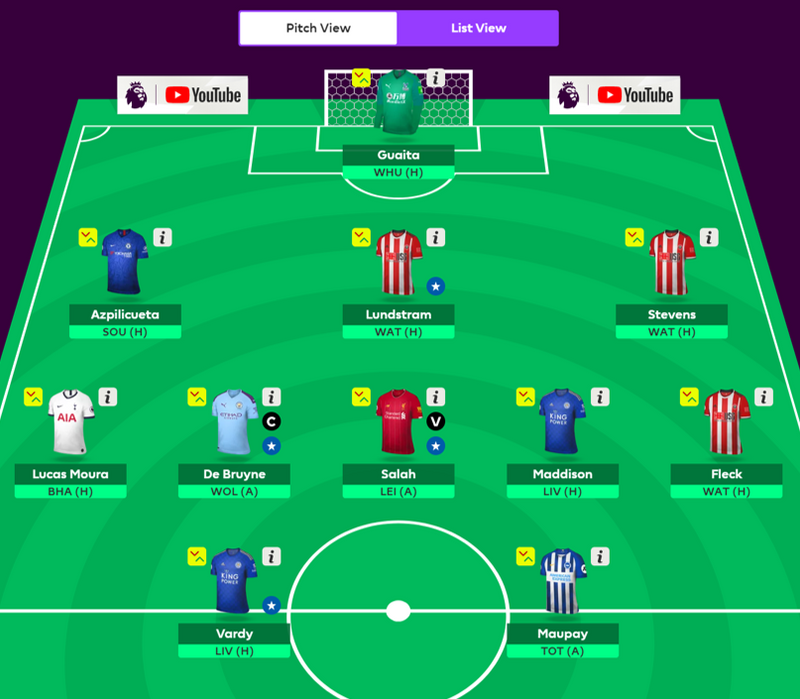

The Regressed Registas. Cost: £79.5m

|

The Neural Netters. Cost: £63.2m

As we see, the two teams are fundamentally different. The regression settles on a conventional 3-5-2 formation, with familiar faces such as Vardy, Lundstram and De Bruyne, which were in fact the three most selected players in GW 18. A great performance against Aston Villa in round 17 paired with a supposedly managable home match against Watford supports the addition of Lundstram's teammates Fleck and Stevens. Vardy and Maddison will hope to shorten the Liverpool lead, while Maupay needs to bounce back from a disappointing home performance against Sheffield United on Saturday. A slightly weaker opponent is likely what gives De Bruyne the edge as captain over Mohamed Salah. The price of the team leaves a comfortable £20.5m for filling up the four spots on the sideline.

The neural network has opted for a refreshing 5-2-3 formation, with large emphasis on Sheffield and Villa defenders. Doherty and Neves will face a tough task in Pep Guadiola's men on Thursday, while Christian Benteke is still waiting for his first goal of the 19/20 season. Trusted with the captain's band, Abraham should have plenty of chances to reignite his old scoring form against the most conceding team of the Premier League season so far. Notably, all players but Martinelli have home matches, which could indicate a substantial preference for this by the model. Finally, despite boasting a rather speculative team, the model remains financially sober and leaves plenty of room in the budget for some decent benchwarmers.

Further work

These models have been built to show the potential value of adding machine learning capabilities to solve problems which require consideration of many factors. The models themselves are fairly basic, and there are several ways to improve them – perhaps by augmenting the input data or through some ensamble learning approach. However, a more interesting discussion is whether this is in fact a problem worth solving with machine learning.

Modeling all possible variables influencing a player's performance in a given Premier League round is not feasible. The problem of setting up a Fantasy draft is, as most complex problems of this sort, an area where expert humans are likely to continue outperforming automated efforts. Nevertheless, the value of quantitative methods as decision support is indisputable. Letting machines do the dirty work – crunching big data sets and discovering seemingly indiscernible patterns – and use this insight as guidance for making human decisions, is probably a more rational approach.

Enjoy Boxing Day, and may the second half of the Fantasy Premier League season treat you well!

1See links below

2The GitHub data is usually published 2-3 days after the last game of the round (which was played yesterday, on the 22nd). Further, since Liverpool-West Ham was postponed, the form data would be incomplete.

3We compare results from our models with the average human score for each round. This implicitly relies on the false premise that all human players can pick a brand-new squad (in practice, use a wildcard) every single round, so the machine scores should ideally be slightly devaluated.

Up next...

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…