Four Definitions of Design

7 min read

·

By Sonja Sarah Porter

·

December 23, 2019

You’ve got this. Your colleague just opened up for the ultimate discussion: “Can you explain this ‘design’ thing to me?” You’ve waited a long time for this moment, biting your tongue every time your whole field is reduced to “making it pretty”. After many years of study and hard work you know what this design thing is now, right? Yet the words escape you, and all those perfect quotes you found online just don’t seem to cut it. You may fall back to describing the value of design, but describing exactly what design is... that’s harder.

There is an ancient Indian proverb about the blind men and the elephant. The men have never seen an elephant before, and when one is placed in front of them each starts experiencing a different part of the elephant…

"“It’s a rope!” says one blind man, feeling the slender length of the elephant’s tail. “No, it’s definitely a tree,” says another, arms around one of the legs. “You’re all mistaken,” says yet another near the tusk, “This is definitely a spear.”"

And so on and so forth. The proverb is often used to illustrate how good we are at claiming absolute truth based on our own limited experiences, while dismissing the truths of others. I find this idea of multiple truths interesting in the pursuit of defining something so complex as design. In researching for this article, I found a variety of approaches to describing design where the perspective, context, and the goals of the author vary. Many designers have attempted to describe design in a simple elevator pitch, yet these simple descriptions only describe a part of the beast. But consider them together, and a greater picture starts to form.

Here are the four descriptions of design I found most useful:

1. The design curriculum

Perhaps the most straight-forward way of describing design would be the way it was described to the designer – through their education. Though design training varies, there are some common themes:

Project-based learning\ Most design schools have a focus on learning design by doing design. It is a hands-on major where students learn by model projects requiring them frame the challenge, ideate and present designs, then receive and give feedback through “Critiques”.

Methodology\ Techniques for generating and exploring numerous concepts, then methodically narrowing down to the best solution.

Insight, research and co-creation\ Designers are taught that the answer always lies with the user. By learning interview techniques, co-creation, facilitation and mapping techniques, designers grow their empathy for users and train to move past their own assumptions and biases.

Storytelling\ Humans respond best to stories – it is how we naturally process and store information. Designers learn to harness this both in text, user flows and to sell concepts.

Aesthetics\ How can shape, line, color, and type affect how we receive and respond to a visual message? How can one lead the eye through a composition, or create different feelings through visual elements?

Visualization\ With a foundation in aesthetics, designers practice to be able to quickly and efficiently turn complex ideas and problems into easy-to-understand visuals through simple sketches and diagrams.

Prototyping\ Prototyping allows designers to test and iterate on concepts in a fast and cheap way.

Even after formal education, designers are often still measured by these attributes. Want to understand a designer? Understand the little professor-voice in their head still nagging about these things.

2. Not engineering or art, but close.

Zooming way out, another approach to describing design is by contrasting it to related disciplines. In the Netflix series Abstract, designer and renaissance woman Neri Oxman presents a diagram of her team’s process, with an interesting perspective on design:

Neri Oxman's Krebs Cycle of Creativity. Source: MIT Spectrum

Oxman’s work with Bio-architecture is at the intersection of design, science, engineering and art, so for her the blurred boundaries of these disciplines has been especially enlightening. She describes how the fields bleed into and inform one another:

"“Science converts information into knowledge. Engineering converts knowledge into utility. Design converts utility into cultural behavior in context. Art takes that cultural behavior and questions our perception of the world.” – Neri Oxman"

In her team’s work, design is defined by the input it needs from neighboring disciplines, and the output it gives to others.

Similarly, way back in 1965 designer Bruce Archer mused about a question that still confuses many today: what is the difference between art and design? Though they may seem similar, they are quite fundamentally different. Think about it… an architect preparing plans for a house – that is design. So is a typographer preparing a page for print. But what about a sculptor, shaping a figure out of clay? Is that design? Archer would argue no – an artist creates, they do not design. For an activity to qualify as “design” there are two requirements:

- A prior formulation of a prescription or model

- The hope or expectation of ultimate embodiment as an artifact

So basically, according to Archer, design is about making plans for something you hope gets made in the future, while art creates the actual thing then and there.

3. The many facets of design

Perhaps one of the greatest challenges in finding one definition of design is the sheer breadth and diversity of design activities, problems being solved, and outputs. At the broadest level, designers could be classified by the medium they work with: physical objects, digital interfaces, visual systems, environments, experiences, etc. While some designers aim to be generalists and deliver all types of design, some specialize. Others find a subset of design they love doing, but can do the rest as well. A multitude of titles have emerged to describe these profiles and the facets of design they work with, with mixed success. This variety can create confusion for their non-design counterparts, especially in trying to find the right designer(s) for their team.

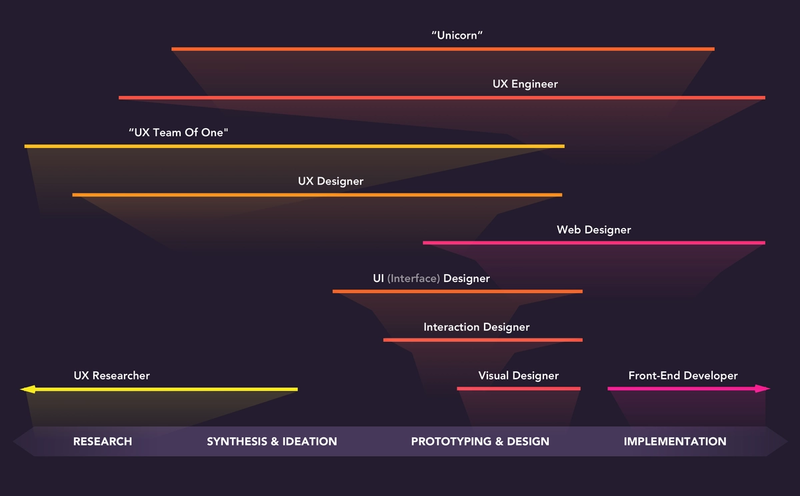

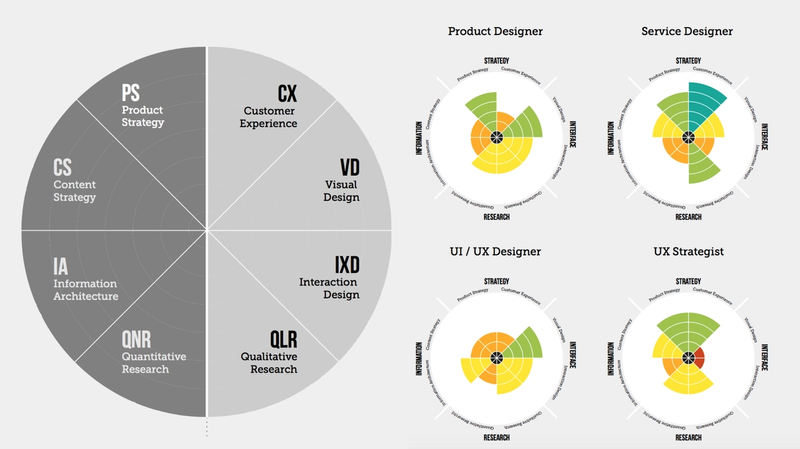

As visual communicators, describing this variety becomes a design problem. Many designers have attempted to describe these different types of designers by visualizing them on a spectrum to provide some clarity. Here are some examples from digital product design, one of many design disciplines:

Jasper Stephenson maps designer titles over a timeline of the project phases they are most involved in. Source: The spectrum of design roles in 2018 | UX Collective

The UX spectrum shows a wide variety of profiles even within UX, depending on their strengths in certain skills. Source: Vitamintalent

4. Design is the questions we ask.

Some would argue that there is one sure-fire way to find the designer on a team – the questions they ask. Your designer is probably the one asking questions like:

- Who is our target audience? What are they trying to achieve? How can I get their input?

- How do people react to, interact with, or use this? What doesn’t work right now?

- What are we trying to achieve? How does this help our users?

- What are we trying to communicate? Is there a way to do it faster, better or in a more unique way?

- How can I get input from subject-matter experts?

- What dependencies (other services, technical systems, laws and regulations, etc.) affect the experience?

Questions are an interesting angle in defining design, as questions are a tangible output of the typical problems design aims to solve – not to mention the core values and philosophies of a designer. Yet they don’t require long training or special tools. They can be asked by anyone, not just the designer. So per this definition, design can still happen without it’s advocate, as long as questions like these are being asked. Interesting.

---

And there you have it – four definitions, each shedding a bit of light on what this “design” thing is. Four not enought? Check out even more below.

Up next...

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…

Loading…